Editorial

- Details

- Editorial

It is exactly 18 years ever since the Nsam fire disaster in Yaounde that claimed the lives of hundreds of innocent Cameroonians. Interestingly, the results of the investigating commission that was appointed by President Biya are still being awaited. Correspondingly, no official ceremony was held on Sunday, February 14, 2016, on the site of the disaster. No word from the 83 year old dictator, no statement from his secretary general at the presidency, nothing came from his so called prime minister and head of government. On Saturday, February 14, 1998, a cargo train that was transporting fuel collided with a tanker loaded with gasoline at the Yaounde 3rd district of Nsam. The two containers each had a capacity of 50 m3, 50 000 liters of gasoline.

Both tanks exploded and as some hungry citizens rushed to recover about 100 000 liters of fuel that had spilled onto the tarmac, a fire erupted from one of the looters who lit a cigarette. It was an unprecedented fracas in our nation's history as a hundreds were declared dead and hundreds burned to ashes. It was termed a national disaster. President Paul Biya, who as usual was out of the country at the time of the tragedy, returned a few days later and created an investigative commission to "shed light on the tragedy." 18 years later, the commission has never made public its findings.

Cameroonians still do not know what was the cause of the disaster. Life had long returned to normal at Nsam and families of the victims were reportedly compensated. Some survivals were supported in several hospitals in the nation's capital. Ever since, no monument has been erected in loving memory of those who died and no official ceremony either. On Sunday, February 14, 2016, no official ceremony took place throughout the national territory and nothing was even mentioned on state radio and television. Biya and his CPDM gang were busy celebrating his 83 years birthday party and Rose Mbole Epie and Co. were enjoying a Valentine's Day party on CRTV's Tam Tam Weekend.

- Details

- Ngwa Bertrand

- Hits: 5033

- Details

- Editorial

On February 13th 2016, lawyers of the Common Law extraction in Cameroon shall converge in Buea for another conference. Of course top on the agenda will be to address the moves currently been taken by some overzealous administrative and judicial authorities to annihilate the common law in Cameroon. At this point, I cannot but jump in to attempt a proposal as to what should be on our minds during that conference. In that vein, I wish to remind my colleagues about the learned Barrister Chief Charles AchalekeTakuon the occasion of the society’s inaugural meeting in Bamenda on Jan 28 2012. On that day, Chief Taku in his keynote addresssaid “…some misguided and gullible political leaders miscomprehend unity (of the two Cameroons) with uniformity and see every facet of public life that promotes and protects freedom and a free society as a threat to their political power.For this reason, they evinced every effort to short-circuit and abort the development and survival of the common law system that has governed much of the free world for centuries. To attain this goal, they put in place a deliberate amorphous system so-called ‘harmonization’, whose purport is to create confusion, put … the common law system under constant threat, then destabilise, and impose a preconceived substitute with an enslaving agenda”.

The common law, “… a system that guarantees judicial remedies like Habeas Corpus, Certiorari, Prohibition, Mandamus and made bail a right rather than a privilege, threatens executive lawlessness and dictatorship,” the erudite and eloquent Chief Taku continued.

At this juncture, the history of the sad and sorry union between the Cameroons comes to mind. Every true chronicler of the Cameroon situation remembers those institutions of Former West Cameroon… Powercam, Cameroon Bank, the West Cameroon Police Force, etc., amongst others that have been killed by the ‘other’ Cameroon. One thinks of how the peoples of English speaking extraction in this so-called union watch helplessly as their kith and kin are being reduced daily, to second-class citizens. Then I ask; will the Cameroon Anglophone Lawyer sit quiet and watch how the tool with which he is supposed to defend his clients, is being eroded and taken away from him? If the Cameroon Common Law Lawyer does not stand up against this, would he be able to stand up for his client? With what? The answers that ruminate to mind, send climes of chilly self-annihilating steps back home and propel me to join Chief Taku and the common law lawyers that are to converge in Bamenda to say an emphatic NO!

I further suggest that the Cameroon common law lawyer must reclaim the ethical legacy of noble lawyers past and neophyte lawyers must be schooled in that wisdom and professional justification. I make bold to state that the current process of harmonization of laws between the civil law and the common law in Cameroon is an attempt at suppressing the latter, to the point of even killing it. As such, while in Bamenda or anywhere in the future, the Cameroon Anglophone lawyer should be able to stand and remain standing while hurling anathemas on the assimilating system which now comes under the disguised form of the so-called harmonisation. The Cameroon common law lawyer must not be like Chinua Achebe’s proverbial adult, who sits and watches the she goat suffer under the pains of child birth. He must be able to say that there is no way that laws and procedures that are to be used in two distinct legal systems could ever be harmonised and be expected to thrive as separate entities. No!

Nowhere in human history has the civil law and common law, be it in their adjectival or procedural forms, have been harmonised! It does not work like that. It has never. And so, shall it never work! There have been classic biases and atrocities committed against the common law system in this country. But lately, the perpetrators of these heinous crimes have executed a sudden somersault with apologies that the real intention is not to exterminate the common law system, but to harmonise the two systems in the now “one Cameroon’. The fact that this traditional adversarial image (as opposed to the French civil law system), still has great currency in the legal profession the world over, has much to do with the equally traditional theory of law from which it draws its shape and justification. For better or for worse, the hallmark is found in their cultivation of rule-craft, -the ability to identify the extant rules of the legal system and apply them to particular situations. The central article of faith of this traditional positivism is that rules are the basic currency of legal transactions and their application can be performed in a professional and objective way.

In my book, the common law is an imposing (and should remain) an imposed structure that has considerable stability, that is operationally determinate in the guidance it extends to the trained lawyer and that is institutionally distinct from the more open-minded disputations around ideological politics. As such, the image of the lawyer-as-hired-hand embraces the idea that the common law in Cameroon, like everywhere in the world, has a life of its own and should neither be politically-myth-informed, nor influenced by governmental policy makers and (mis)managers.

In this sense, any practice that craves and expects professional recognition must be seen to take the common law seriously in the sense that it pursues clients’ interests through extant rules, procedures and values of law: overt politicisation is severely frowned at. Again, in my book, this is a proud unapologetic and defiant defence of the Rule of Law which must now become pax-Kamaruna. And if this must be, then it must be the face of the Cameroon Anglophone Lawyer.

The common law lawyer in Cameroon today must cut a niche for himself. He must stand out clearly in exhibition of the notion of the lawyer as a civic campaigner. He must build a pyramid of honour, probity and humaneness and impose himself up there, especially in the face of the present condition of the peoples of English speaking extraction in this so called union of the two Cameroons. He must be a goad and a gadfly to his suffering kith and kin. The common law lawyer must speak out against bribery and corruption, stand for the down-trodden and defend his kindred who are now caught up in this quagmire of Quisling-Iscariots. (I have taken liberties here with the late Dr. Bate Besong of the ObassinjomWorrior fame). Oh yes, we must deny to be Heweit! Litigation and adjudication are much more value-laden and results-oriented than traditionalists suppose. Consequently, the common law lawyer must take an appropriate share of the responsibility for those values and results. At the very least, he must engage in the struggle to make the legal process the best that it can be for the benefit of those who live under its directives, particularly the disadvantaged and disenfranchised.

As much as lawyers are officers of the law, they are also agents of the people: they cannot afford to sit quiet in the face of such blatant rape being meted out with impunity and excruciating pain against their lot and institutions. With our present situation, the Cameroon common law lawyer cannot assume a non-committal position. He must be militant and assume a much more pedestrian approach in defence of the law. My take is that the Cameroon judicial system has much to emulate from the Canadian experience. Like Cameroon, Canada is both bilingual and bi-jural. While the civil law system, informed by the codified Napoleonic laws obtains in the Francophone region of Canada, the common law system obtains in Anglophone Canada. These two have co-existed ever since the Canadian Federation was founded.

None of the two systems has attempted to swallow or engulf the other! Both the Common law and the civil law thrive side-by-side, and so well in Canada. So why can it not be so in the Cameroons? The civil law and the common law are like equity and the law itself. Professor Kisob I remember once said that they are like two streams that run through the same channel but their waters don’t mix. This is the sermon that the Cameroon Anglophone lawyer must preach ex-cathedra, to the powers that be! In July 1995, 16 French speaking countries in Africa ratified the OHADA Treaties. These treaties were to harmonize business law in Africa. Cameroon was amongst them. All of these countries have the civil law system as their system of law. The law stated that the working language of the OHADA was French. As expected, the Yaounde junta attempted to have this law operate in English speaking Cameroon, but the common law lawyers (from both the bench and the bar) stood like one man and said NO!They objected to the applicability of the OHADA as it was. Not long, English language was added as another working language of the said law. This was a eureka moment for the common law system in Cameroon. If the common law lawyer could force the English language on the French speaking countries of the sub-region, then it can stop the wanton rape now being done on its system of law practice. Yes we can.

* Parts of this article were first published in The NewBroom Magazine. Its author, TANYI-MBIANYOR SAMUEL TABI is a Common Law Lawyer who read law in Toronto and Yaounde. A member of both the Cameroon and Canadian bar Associations, he is currently a research student at Walden University.

- Details

- Ngwa Bertrand

- Hits: 4119

- Details

- Editorial

On February 13th 2016, lawyers of the Common Law extraction in Cameroon shall converge in Buea for another conference. Of course top on the agenda will be to address the moves currently been taken by some overzealous administrative and judicial authorities to annihilate the common law in Cameroon. At this point, I cannot but jump in to attempt a proposal as to what should be on our minds during that conference. In that vein, I wish to remind my colleagues about the learned Barrister Chief Charles AchalekeTakuon the occasion of the society’s inaugural meeting in Bamenda on Jan 28 2012. On that day, Chief Taku in his keynote addresssaid “…some misguided and gullible political leaders miscomprehend unity (of the two Cameroons) with uniformity and see every facet of public life that promotes and protects freedom and a free society as a threat to their political power.For this reason, they evinced every effort to short-circuit and abort the development and survival of the common law system that has governed much of the free world for centuries. To attain this goal, they put in place a deliberate amorphous system so-called ‘harmonization’, whose purport is to create confusion, put … the common law system under constant threat, then destabilise, and impose a preconceived substitute with an enslaving agenda”.

The common law, “… a system that guarantees judicial remedies like Habeas Corpus, Certiorari, Prohibition, Mandamus and made bail a right rather than a privilege, threatens executive lawlessness and dictatorship,” the erudite and eloquent Chief Taku continued.

At this juncture, the history of the sad and sorry union between the Cameroons comes to mind. Every true chronicler of the Cameroon situation remembers those institutions of Former West Cameroon… Powercam, Cameroon Bank, the West Cameroon Police Force, etc., amongst others that have been killed by the ‘other’ Cameroon. One thinks of how the peoples of English speaking extraction in this so-called union watch helplessly as their kith and kin are being reduced daily, to second-class citizens. Then I ask; will the Cameroon Anglophone Lawyer sit quiet and watch how the tool with which he is supposed to defend his clients, is being eroded and taken away from him? If the Cameroon Common Law Lawyer does not stand up against this, would he be able to stand up for his client? With what? The answers that ruminate to mind, send climes of chilly self-annihilating steps back home and propel me to join Chief Taku and the common law lawyers that are to converge in Bamenda to say an emphatic NO!

I further suggest that the Cameroon common law lawyer must reclaim the ethical legacy of noble lawyers past and neophyte lawyers must be schooled in that wisdom and professional justification. I make bold to state that the current process of harmonization of laws between the civil law and the common law in Cameroon is an attempt at suppressing the latter, to the point of even killing it. As such, while in Bamenda or anywhere in the future, the Cameroon Anglophone lawyer should be able to stand and remain standing while hurling anathemas on the assimilating system which now comes under the disguised form of the so-called harmonisation. The Cameroon common law lawyer must not be like Chinua Achebe’s proverbial adult, who sits and watches the she goat suffer under the pains of child birth. He must be able to say that there is no way that laws and procedures that are to be used in two distinct legal systems could ever be harmonised and be expected to thrive as separate entities. No!

Nowhere in human history has the civil law and common law, be it in their adjectival or procedural forms, have been harmonised! It does not work like that. It has never. And so, shall it never work! There have been classic biases and atrocities committed against the common law system in this country. But lately, the perpetrators of these heinous crimes have executed a sudden somersault with apologies that the real intention is not to exterminate the common law system, but to harmonise the two systems in the now “one Cameroon’. The fact that this traditional adversarial image (as opposed to the French civil law system), still has great currency in the legal profession the world over, has much to do with the equally traditional theory of law from which it draws its shape and justification. For better or for worse, the hallmark is found in their cultivation of rule-craft, -the ability to identify the extant rules of the legal system and apply them to particular situations. The central article of faith of this traditional positivism is that rules are the basic currency of legal transactions and their application can be performed in a professional and objective way.

In my book, the common law is an imposing (and should remain) an imposed structure that has considerable stability, that is operationally determinate in the guidance it extends to the trained lawyer and that is institutionally distinct from the more open-minded disputations around ideological politics. As such, the image of the lawyer-as-hired-hand embraces the idea that the common law in Cameroon, like everywhere in the world, has a life of its own and should neither be politically-myth-informed, nor influenced by governmental policy makers and (mis)managers.

In this sense, any practice that craves and expects professional recognition must be seen to take the common law seriously in the sense that it pursues clients’ interests through extant rules, procedures and values of law: overt politicisation is severely frowned at. Again, in my book, this is a proud unapologetic and defiant defence of the Rule of Law which must now become pax-Kamaruna. And if this must be, then it must be the face of the Cameroon Anglophone Lawyer.

The common law lawyer in Cameroon today must cut a niche for himself. He must stand out clearly in exhibition of the notion of the lawyer as a civic campaigner. He must build a pyramid of honour, probity and humaneness and impose himself up there, especially in the face of the present condition of the peoples of English speaking extraction in this so called union of the two Cameroons. He must be a goad and a gadfly to his suffering kith and kin. The common law lawyer must speak out against bribery and corruption, stand for the down-trodden and defend his kindred who are now caught up in this quagmire of Quisling-Iscariots. (I have taken liberties here with the late Dr. Bate Besong of the ObassinjomWorrior fame). Oh yes, we must deny to be Heweit! Litigation and adjudication are much more value-laden and results-oriented than traditionalists suppose. Consequently, the common law lawyer must take an appropriate share of the responsibility for those values and results. At the very least, he must engage in the struggle to make the legal process the best that it can be for the benefit of those who live under its directives, particularly the disadvantaged and disenfranchised.

As much as lawyers are officers of the law, they are also agents of the people: they cannot afford to sit quiet in the face of such blatant rape being meted out with impunity and excruciating pain against their lot and institutions. With our present situation, the Cameroon common law lawyer cannot assume a non-committal position. He must be militant and assume a much more pedestrian approach in defence of the law. My take is that the Cameroon judicial system has much to emulate from the Canadian experience. Like Cameroon, Canada is both bilingual and bi-jural. While the civil law system, informed by the codified Napoleonic laws obtains in the Francophone region of Canada, the common law system obtains in Anglophone Canada. These two have co-existed ever since the Canadian Federation was founded.

None of the two systems has attempted to swallow or engulf the other! Both the Common law and the civil law thrive side-by-side, and so well in Canada. So why can it not be so in the Cameroons? The civil law and the common law are like equity and the law itself. Professor Kisob I remember once said that they are like two streams that run through the same channel but their waters don’t mix. This is the sermon that the Cameroon Anglophone lawyer must preach ex-cathedra, to the powers that be! In July 1995, 16 French speaking countries in Africa ratified the OHADA Treaties. These treaties were to harmonize business law in Africa. Cameroon was amongst them. All of these countries have the civil law system as their system of law. The law stated that the working language of the OHADA was French. As expected, the Yaounde junta attempted to have this law operate in English speaking Cameroon, but the common law lawyers (from both the bench and the bar) stood like one man and said NO!They objected to the applicability of the OHADA as it was. Not long, English language was added as another working language of the said law. This was a eureka moment for the common law system in Cameroon. If the common law lawyer could force the English language on the French speaking countries of the sub-region, then it can stop the wanton rape now being done on its system of law practice. Yes we can.

* Parts of this article were first published in The NewBroom Magazine. Its author, TANYI-MBIANYOR SAMUEL TABI is a Common Law Lawyer who read law in Toronto and Yaounde. A member of both the Cameroon and Canadian bar Associations, he is currently a research student at Walden University.

- Details

- Ngwa Bertrand

- Hits: 1993

- Details

- Editorial

On February 13th 2016, lawyers of the Common Law extraction in Cameroon shall converge in Buea for another conference. Of course top on the agenda will be to address the moves currently been taken by some overzealous administrative and judicial authorities to annihilate the common law in Cameroon. At this point, I cannot but jump in to attempt a proposal as to what should be on our minds during that conference. In that vein, I wish to remind my colleagues about the learned Barrister Chief Charles AchalekeTakuon the occasion of the society’s inaugural meeting in Bamenda on Jan 28 2012. On that day, Chief Taku in his keynote addresssaid “…some misguided and gullible political leaders miscomprehend unity (of the two Cameroons) with uniformity and see every facet of public life that promotes and protects freedom and a free society as a threat to their political power.For this reason, they evinced every effort to short-circuit and abort the development and survival of the common law system that has governed much of the free world for centuries. To attain this goal, they put in place a deliberate amorphous system so-called ‘harmonization’, whose purport is to create confusion, put … the common law system under constant threat, then destabilise, and impose a preconceived substitute with an enslaving agenda”.

The common law, “… a system that guarantees judicial remedies like Habeas Corpus, Certiorari, Prohibition, Mandamus and made bail a right rather than a privilege, threatens executive lawlessness and dictatorship,” the erudite and eloquent Chief Taku continued.

At this juncture, the history of the sad and sorry union between the Cameroons comes to mind. Every true chronicler of the Cameroon situation remembers those institutions of Former West Cameroon… Powercam, Cameroon Bank, the West Cameroon Police Force, etc., amongst others that have been killed by the ‘other’ Cameroon. One thinks of how the peoples of English speaking extraction in this so-called union watch helplessly as their kith and kin are being reduced daily, to second-class citizens. Then I ask; will the Cameroon Anglophone Lawyer sit quiet and watch how the tool with which he is supposed to defend his clients, is being eroded and taken away from him? If the Cameroon Common Law Lawyer does not stand up against this, would he be able to stand up for his client? With what? The answers that ruminate to mind, send climes of chilly self-annihilating steps back home and propel me to join Chief Taku and the common law lawyers that are to converge in Bamenda to say an emphatic NO!

I further suggest that the Cameroon common law lawyer must reclaim the ethical legacy of noble lawyers past and neophyte lawyers must be schooled in that wisdom and professional justification. I make bold to state that the current process of harmonization of laws between the civil law and the common law in Cameroon is an attempt at suppressing the latter, to the point of even killing it. As such, while in Bamenda or anywhere in the future, the Cameroon Anglophone lawyer should be able to stand and remain standing while hurling anathemas on the assimilating system which now comes under the disguised form of the so-called harmonisation. The Cameroon common law lawyer must not be like Chinua Achebe’s proverbial adult, who sits and watches the she goat suffer under the pains of child birth. He must be able to say that there is no way that laws and procedures that are to be used in two distinct legal systems could ever be harmonised and be expected to thrive as separate entities. No!

Nowhere in human history has the civil law and common law, be it in their adjectival or procedural forms, have been harmonised! It does not work like that. It has never. And so, shall it never work! There have been classic biases and atrocities committed against the common law system in this country. But lately, the perpetrators of these heinous crimes have executed a sudden somersault with apologies that the real intention is not to exterminate the common law system, but to harmonise the two systems in the now “one Cameroon’. The fact that this traditional adversarial image (as opposed to the French civil law system), still has great currency in the legal profession the world over, has much to do with the equally traditional theory of law from which it draws its shape and justification. For better or for worse, the hallmark is found in their cultivation of rule-craft, -the ability to identify the extant rules of the legal system and apply them to particular situations. The central article of faith of this traditional positivism is that rules are the basic currency of legal transactions and their application can be performed in a professional and objective way.

In my book, the common law is an imposing (and should remain) an imposed structure that has considerable stability, that is operationally determinate in the guidance it extends to the trained lawyer and that is institutionally distinct from the more open-minded disputations around ideological politics. As such, the image of the lawyer-as-hired-hand embraces the idea that the common law in Cameroon, like everywhere in the world, has a life of its own and should neither be politically-myth-informed, nor influenced by governmental policy makers and (mis)managers.

In this sense, any practice that craves and expects professional recognition must be seen to take the common law seriously in the sense that it pursues clients’ interests through extant rules, procedures and values of law: overt politicisation is severely frowned at. Again, in my book, this is a proud unapologetic and defiant defence of the Rule of Law which must now become pax-Kamaruna. And if this must be, then it must be the face of the Cameroon Anglophone Lawyer.

The common law lawyer in Cameroon today must cut a niche for himself. He must stand out clearly in exhibition of the notion of the lawyer as a civic campaigner. He must build a pyramid of honour, probity and humaneness and impose himself up there, especially in the face of the present condition of the peoples of English speaking extraction in this so called union of the two Cameroons. He must be a goad and a gadfly to his suffering kith and kin. The common law lawyer must speak out against bribery and corruption, stand for the down-trodden and defend his kindred who are now caught up in this quagmire of Quisling-Iscariots. (I have taken liberties here with the late Dr. Bate Besong of the ObassinjomWorrior fame). Oh yes, we must deny to be Heweit! Litigation and adjudication are much more value-laden and results-oriented than traditionalists suppose. Consequently, the common law lawyer must take an appropriate share of the responsibility for those values and results. At the very least, he must engage in the struggle to make the legal process the best that it can be for the benefit of those who live under its directives, particularly the disadvantaged and disenfranchised.

As much as lawyers are officers of the law, they are also agents of the people: they cannot afford to sit quiet in the face of such blatant rape being meted out with impunity and excruciating pain against their lot and institutions. With our present situation, the Cameroon common law lawyer cannot assume a non-committal position. He must be militant and assume a much more pedestrian approach in defence of the law. My take is that the Cameroon judicial system has much to emulate from the Canadian experience. Like Cameroon, Canada is both bilingual and bi-jural. While the civil law system, informed by the codified Napoleonic laws obtains in the Francophone region of Canada, the common law system obtains in Anglophone Canada. These two have co-existed ever since the Canadian Federation was founded.

None of the two systems has attempted to swallow or engulf the other! Both the Common law and the civil law thrive side-by-side, and so well in Canada. So why can it not be so in the Cameroons? The civil law and the common law are like equity and the law itself. Professor Kisob I remember once said that they are like two streams that run through the same channel but their waters don’t mix. This is the sermon that the Cameroon Anglophone lawyer must preach ex-cathedra, to the powers that be! In July 1995, 16 French speaking countries in Africa ratified the OHADA Treaties. These treaties were to harmonize business law in Africa. Cameroon was amongst them. All of these countries have the civil law system as their system of law. The law stated that the working language of the OHADA was French. As expected, the Yaounde junta attempted to have this law operate in English speaking Cameroon, but the common law lawyers (from both the bench and the bar) stood like one man and said NO!They objected to the applicability of the OHADA as it was. Not long, English language was added as another working language of the said law. This was a eureka moment for the common law system in Cameroon. If the common law lawyer could force the English language on the French speaking countries of the sub-region, then it can stop the wanton rape now being done on its system of law practice. Yes we can.

* Parts of this article were first published in The NewBroom Magazine. Its author, TANYI-MBIANYOR SAMUEL TABI is a Common Law Lawyer who read law in Toronto and Yaounde. A member of both the Cameroon and Canadian bar Associations, he is currently a research student at Walden University.

- Details

- Ngwa Bertrand

- Hits: 1782

- Details

- Editorial

On February 13th 2016, lawyers of the Common Law extraction in Cameroon shall converge in Buea for another conference. Of course top on the agenda will be to address the moves currently been taken by some overzealous administrative and judicial authorities to annihilate the common law in Cameroon. At this point, I cannot but jump in to attempt a proposal as to what should be on our minds during that conference. In that vein, I wish to remind my colleagues about the learned Barrister Chief Charles AchalekeTakuon the occasion of the society’s inaugural meeting in Bamenda on Jan 28 2012. On that day, Chief Taku in his keynote addresssaid “…some misguided and gullible political leaders miscomprehend unity (of the two Cameroons) with uniformity and see every facet of public life that promotes and protects freedom and a free society as a threat to their political power.For this reason, they evinced every effort to short-circuit and abort the development and survival of the common law system that has governed much of the free world for centuries. To attain this goal, they put in place a deliberate amorphous system so-called ‘harmonization’, whose purport is to create confusion, put … the common law system under constant threat, then destabilise, and impose a preconceived substitute with an enslaving agenda”.

The common law, “… a system that guarantees judicial remedies like Habeas Corpus, Certiorari, Prohibition, Mandamus and made bail a right rather than a privilege, threatens executive lawlessness and dictatorship,” the erudite and eloquent Chief Taku continued.

At this juncture, the history of the sad and sorry union between the Cameroons comes to mind. Every true chronicler of the Cameroon situation remembers those institutions of Former West Cameroon… Powercam, Cameroon Bank, the West Cameroon Police Force, etc., amongst others that have been killed by the ‘other’ Cameroon. One thinks of how the peoples of English speaking extraction in this so-called union watch helplessly as their kith and kin are being reduced daily, to second-class citizens. Then I ask; will the Cameroon Anglophone Lawyer sit quiet and watch how the tool with which he is supposed to defend his clients, is being eroded and taken away from him? If the Cameroon Common Law Lawyer does not stand up against this, would he be able to stand up for his client? With what? The answers that ruminate to mind, send climes of chilly self-annihilating steps back home and propel me to join Chief Taku and the common law lawyers that are to converge in Bamenda to say an emphatic NO!

I further suggest that the Cameroon common law lawyer must reclaim the ethical legacy of noble lawyers past and neophyte lawyers must be schooled in that wisdom and professional justification. I make bold to state that the current process of harmonization of laws between the civil law and the common law in Cameroon is an attempt at suppressing the latter, to the point of even killing it. As such, while in Bamenda or anywhere in the future, the Cameroon Anglophone lawyer should be able to stand and remain standing while hurling anathemas on the assimilating system which now comes under the disguised form of the so-called harmonisation. The Cameroon common law lawyer must not be like Chinua Achebe’s proverbial adult, who sits and watches the she goat suffer under the pains of child birth. He must be able to say that there is no way that laws and procedures that are to be used in two distinct legal systems could ever be harmonised and be expected to thrive as separate entities. No!

Nowhere in human history has the civil law and common law, be it in their adjectival or procedural forms, have been harmonised! It does not work like that. It has never. And so, shall it never work! There have been classic biases and atrocities committed against the common law system in this country. But lately, the perpetrators of these heinous crimes have executed a sudden somersault with apologies that the real intention is not to exterminate the common law system, but to harmonise the two systems in the now “one Cameroon’. The fact that this traditional adversarial image (as opposed to the French civil law system), still has great currency in the legal profession the world over, has much to do with the equally traditional theory of law from which it draws its shape and justification. For better or for worse, the hallmark is found in their cultivation of rule-craft, -the ability to identify the extant rules of the legal system and apply them to particular situations. The central article of faith of this traditional positivism is that rules are the basic currency of legal transactions and their application can be performed in a professional and objective way.

In my book, the common law is an imposing (and should remain) an imposed structure that has considerable stability, that is operationally determinate in the guidance it extends to the trained lawyer and that is institutionally distinct from the more open-minded disputations around ideological politics. As such, the image of the lawyer-as-hired-hand embraces the idea that the common law in Cameroon, like everywhere in the world, has a life of its own and should neither be politically-myth-informed, nor influenced by governmental policy makers and (mis)managers.

In this sense, any practice that craves and expects professional recognition must be seen to take the common law seriously in the sense that it pursues clients’ interests through extant rules, procedures and values of law: overt politicisation is severely frowned at. Again, in my book, this is a proud unapologetic and defiant defence of the Rule of Law which must now become pax-Kamaruna. And if this must be, then it must be the face of the Cameroon Anglophone Lawyer.

The common law lawyer in Cameroon today must cut a niche for himself. He must stand out clearly in exhibition of the notion of the lawyer as a civic campaigner. He must build a pyramid of honour, probity and humaneness and impose himself up there, especially in the face of the present condition of the peoples of English speaking extraction in this so called union of the two Cameroons. He must be a goad and a gadfly to his suffering kith and kin. The common law lawyer must speak out against bribery and corruption, stand for the down-trodden and defend his kindred who are now caught up in this quagmire of Quisling-Iscariots. (I have taken liberties here with the late Dr. Bate Besong of the ObassinjomWorrior fame). Oh yes, we must deny to be Heweit! Litigation and adjudication are much more value-laden and results-oriented than traditionalists suppose. Consequently, the common law lawyer must take an appropriate share of the responsibility for those values and results. At the very least, he must engage in the struggle to make the legal process the best that it can be for the benefit of those who live under its directives, particularly the disadvantaged and disenfranchised.

As much as lawyers are officers of the law, they are also agents of the people: they cannot afford to sit quiet in the face of such blatant rape being meted out with impunity and excruciating pain against their lot and institutions. With our present situation, the Cameroon common law lawyer cannot assume a non-committal position. He must be militant and assume a much more pedestrian approach in defence of the law. My take is that the Cameroon judicial system has much to emulate from the Canadian experience. Like Cameroon, Canada is both bilingual and bi-jural. While the civil law system, informed by the codified Napoleonic laws obtains in the Francophone region of Canada, the common law system obtains in Anglophone Canada. These two have co-existed ever since the Canadian Federation was founded.

None of the two systems has attempted to swallow or engulf the other! Both the Common law and the civil law thrive side-by-side, and so well in Canada. So why can it not be so in the Cameroons? The civil law and the common law are like equity and the law itself. Professor Kisob I remember once said that they are like two streams that run through the same channel but their waters don’t mix. This is the sermon that the Cameroon Anglophone lawyer must preach ex-cathedra, to the powers that be! In July 1995, 16 French speaking countries in Africa ratified the OHADA Treaties. These treaties were to harmonize business law in Africa. Cameroon was amongst them. All of these countries have the civil law system as their system of law. The law stated that the working language of the OHADA was French. As expected, the Yaounde junta attempted to have this law operate in English speaking Cameroon, but the common law lawyers (from both the bench and the bar) stood like one man and said NO!They objected to the applicability of the OHADA as it was. Not long, English language was added as another working language of the said law. This was a eureka moment for the common law system in Cameroon. If the common law lawyer could force the English language on the French speaking countries of the sub-region, then it can stop the wanton rape now being done on its system of law practice. Yes we can.

* Parts of this article were first published in The NewBroom Magazine. Its author, TANYI-MBIANYOR SAMUEL TABI is a Common Law Lawyer who read law in Toronto and Yaounde. A member of both the Cameroon and Canadian bar Associations, he is currently a research student at Walden University.

- Details

- Ngwa Bertrand

- Hits: 1823

- Details

- Editorial

After Reunification there was need to mobilize the youths of the nation across the two banks of the Mungo. It is difficult to fully grasp the concept of Youth Day today without throwing a retrospective eye back into the late forties and the early fifties when Cameroonian students studying at that time in European Universities met regularly, irrespective of where they were studying, to talk about the unity of Cameroon. The recent book published by Senator Victor E. Mukete who, incidentally is also the Paramount Ruler of the Bafaws and a first-hand witness of the early years of Cameroonian nationalism, is very instructive for those interested in early Cameroonian nationalism but, above all, the role of the youth in the process of enhancing the building of the Cameroonian nation of which we are beneficiaries today. The traditional ruler, in his book (“My Odyssey”) vividly recounts the various meetings organized by students studying on the both sides of the English Channel, very often overcoming language difficulties with the ultimate desire being solely to get the fragmented parts of the territory of Cameroon, as it was before the division following the First World War, back together into a united political entity.

The institution of Youth Day, as a national observance day in Cameroon, is very much predicated on this desire even if events leading to its institutionalization were not necessarily youth-oriented, but political. The Plebiscite organized by the United Nations Organisation on February 11, 1961 to determine the future of the two Cameroonian territories – Southern Cameroons and Northern Cameroons were not of the taste of then President Ahmadou Ahidjo who would have wished that the plebiscite be organized jointly, rather than separately with one plebiscite in Northern Cameroon and the other in Southern Cameroons. The overall result would have given a victory for reunification with Cameroon, the fatherland at the time, but the separate organization produced a result in favour of Reunification with the then La République du Cameroun for Southern Cameroon and integration with Nigeria for the Northern Cameroon. (233, 571 votes for and 97, 741 votes against union with La République du Cameroun in Southern Cameroon and 97 659 for and 146, 296 against union in Northern Cameroon) For Ahidjo, this was a national catastrophe to the extent that the proclamation of the plebiscite results – February 11, 1961 – was a national day of mourning.

For the next few years following Reunification, the evocation of February 11 sent back sad memories until a mission sent to the then West Cameroon from the Youth Service of the Federal Ministry of Education, Youth, Sports and Popular Education in Yaounde came back with a report, after examining the functioning of youth services in the Federated State of West Cameroon, made proposals as to the need for the creation of a national day devoted to youth. The Federal President acquiesced and thus was formalized; the creation of Youth Day whose 50th anniversary the nation commemorates today. In declaring the day, President Ahmadou Ahidjo had decided to shoot two birds with one stone: on the one hand, keeping the Plebiscite victory alive by observing it from a more positive side rather than only remembering the date from the perspective of the loss of territory.

The plebiscite result could never be revoked as seen from the answer he got following his protest to the United Nations; and on the other hand, consolidating the new-found unity between the two political entities of East and West Cameroon by providing a meeting platform within which youths from the two sides of the Mungo could express themselves. For example, at the very beginnings of the Youth Day, an entire month was devoted to youth activities preceding the Day, but because of the high toll such a long period took on the national economy and the much learning time sacrificed by youths of school going age, the period was brought down to one week as is the case today. Looking back fifty years ago, one must acknowledge that the political gains of Youth Day have been far-reaching even if simply limited to the fact that they have not only brought the nation’s youth closer, but have also provided the opportunity to bring youth problems to the discussion table.

- Details

- Elangwe Pauline

- Hits: 3599

Local News

- Details

- Society

Kribi II: Man Caught Allegedly Abusing Child

- News Team

- 14.Sep.2025

- Details

- Society

Back to School 2025/2026 – Spotlight on Bamenda & Nkambe

- News Team

- 08.Sep.2025

- Details

- Society

Cameroon 2025: From Kamto to Biya: Longue Longue’s political flip shocks supporters

- News Team

- 08.Sep.2025

- Details

- Society

Meiganga bus crash spotlights Cameroon’s road safety crisis

- News Team

- 05.Sep.2025

EditorialView all

- Details

- Editorial

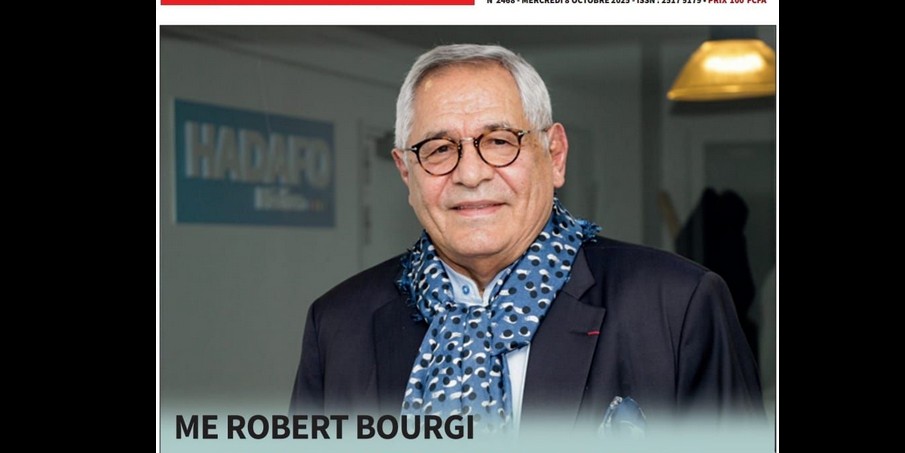

Robert Bourgi Turns on Paul Biya, Declares Him a Political Corpse

- News Team

- 10.Oct.2025

- Details

- Editorial

Heat in Maroua: What Biya’s Return Really Signals

- News Team

- 08.Oct.2025

- Details

- Editorial

Issa Tchiroma: Charles Mambo’s “Change Candidate” for Cameroon

- News Team

- 11.Sep.2025

- Details

- Editorial