Editorial

- Details

- Editorial

A roundtable, held last week at the Institute of African Studies reports that the Nigerian government's "...campaigns have not addressed their plans for combating the growing insecurity that has left Nigerians living in fear, and paralyzed educational and economic activities in large swaths of Northeastern Nigeria." A string of terrorist attacks have occurred as Nigeria has struggled to build a functional and coherent response. Fortunately, there is a science-based approach to create societal coherence that can protect Nigeria from both internal and external threats. It is called Invincible Defense Technology (IDT) because it assures invincibility, peace, and even economic progress, to the nation and the military that employ it.

Invincible Defense Technology (IDT), a Proven, State-of-the-Art, Non-violent Military Solution

The IDT approach to defense has its basis in a radically new preventive model that has been thoroughly field-tested in numerous world battlegrounds. This approach results in rapid reduction of individual, societal and national collective stress. Its methods have been proven and adopted as part of the training of America’s future commanders at Norwich University, a nationally respected and oldest military academy in the USA (see also the YouTube video “Meditation Improves Performance at Military University” and the Official Homepage of the US Army). IDT is further validated by 23 peer-reviewed studies carried out in both developed and developing nations. Its coherence-creating effect has also been documented on a global scale in a study published in the Journal of Offender Rehabilitation. When large assemblies of civilian IDT experts gathered during the years 1983 - 1985, international conflict decreased 32%, terrorism-related casualties decreased 72%, and overall violence was reduced in nations without intrusion by other governments.

IDT is totally unlike any other defense technology because it does not use violence in an attempt to quell violence. It is a more civilized approach, one especially worthy of nations that abhor violence as a means to power. IDT uniquely goes to the root cause of violence - the built-up stress in the individual and collective consciousness. Scientists have evidence that high levels of collective societal stress are the underlying cause of war, violence, crime and terrorism. When the IDT methodology is applied, stress levels throughout the population are rapidly reduced. In an environment of lowered stress even staunch adversaries find ways to cooperate and overcome long-standing differences.

IDT Reduces Societal Stress

IDT uniquely neutralizes the underlying power base of contending groups, which is the stress, frustration and civil dissatisfaction prevailing in the general population. By eliminating the root cause of insurgency, violent outbreaks are pre-empted and prevented. IDT is effective because it gets to the heart of the matter. Terrorism often thrives in nations in which decades or even centuries of under-employment, poverty, and hunger have created a huge societal weight of stress, frustration and endemic unhappiness. This inevitably finds expression in acts of terrorism, civil unrest, social violence, and a downward spiral of economic degradation.

A specially trained military unit, an “IDT Prevention Wing of the Military” uses IDT to reduce stress in the national collective consciousness. IDT could also be introduced into other large groups such as the police forces, or militias. As the stress and frustration ease, the population is more capable of finding orderly and constructive solutions to their problems.

Experience with IDT in other war-torn nations demonstrated increases in economic incentive and growth. Entrepreneurship and individual creativity also increased. With increased civic calm, people's aspirations are raised and a more productive and balanced society emerges. Such a society abhors violence as a means for change or as an expression of discontent. With this, the ground for terrorism is eliminated. What is more fascinating, this change takes place within a few days or weeks after IDT is introduced. The changes are measurable from such statistics as crime rates, accidents, hospital admissions, infant mortality, etc.

Rapid Transformation Through IDT

The daily routine for the IDT military personnel includes the nonreligious practice of the Transcendental Meditation® program along with its advanced form, the TM-Sidhi program. As a societal coherence-creating military unit, they practice these programs twice a day, seven days a week, preferably in a secure location near the targeted population. Such coherence-creating groups have achieved positive benefits in society, shown statistically, in a short time. Modern statistical methods used in this research show a low probability of any explanation other than a causal influence of the technology. The IDT approach has been used during wartime resulting in the reduction of fighting, a decreased number of deaths and casualties, and an improvement in progress toward resolving the conflict peacefully. The war in Lebanon in 1983 was dramatically impacted in a peaceful way by an IDT Intervention Group. A thoroughly documented study of this phenomenon was published in the Journal of Conflict Resolution, and summaries of follow-up studies were published in the Journal of Social Behavior and Personality and the Journal of Scientific Exploration.

Summary

IDT works by utilizing our natural human brain mechanics, the most powerful natural resource possessed by every nation on earth. The beneficial transformational effects of IDT have been statistically proven numerous times to decrease and prevent violence and terrorism, and boost the economy. IDT defense technology supercedes all other known defense technologies (which are based on electronic, chemical and/or nuclear forces). These old, fear-based modalities are ultimately self-destructive for any nation, and for the human race as a whole, and must be replaced with IDT. So far, IDT is the only known, proven constructive approach. The military that deploys this powerful, human-resource-based technology disallows negative trends and prevents enemies from arising, and as a result, it has no enemies. No enemies mean no war, terrorism and no insurgency.

The Time for Action is now

IDT is the twenty-first century's leading-edge defense system. If Nigeria establishes IDT Prevention Wings of the Military, they will ease high tensions, reverse mistrust, crush hatred, create stability and permanently prevent war and terrorism. Extensive scientific research objectively says, "Yes, the system works." Why not use it in Nigeria? Time is running out. The best time to act is now, before Nigeria's perilous situation worsens.

Dr. David Leffler was a member of the US Air Force for nearly nine years. He served as an Associate of the Proteus Management Group at the Center for Strategic Leadership, US Army War College. He now serves as the Executive Director at the Center for Advanced Military Sciences (CAMS) in Fairfield Iowa and teaches IDT.

Contact Dr. David Leffler at http://www.davidleffler.com

|

|

- Details

- Ngwa Bertrand

- Hits: 1557

- Details

- Editorial

Is Africa slowly turning the rhetoric of democracy into action? The Constitutive Act of the African Union (AU), which introduced to the continental body the values of democracy, rule of law and constitutionalism, is 13 years old. And its prohibition of seizing power unconstitutionally goes back even earlier to 2000, preceding the AU.

But the AU created a two-tier ranking of values, as Solomon Ayele Dersso, Head of the Peace and Security Council (PSC) programme at the Institute of Security Studies (ISS), pointed out at a seminar in Addis Ababa this week. The AU implicitly ranked the prohibition against unconstitutional changes of government as a higher value by enforcing it with the sanction of suspension from membership of the AU. It attached no sanction at all to undemocratic, illegal and unconstitutional behaviour more generally. The ban on unconstitutional changes of government was almost entirely interpreted as a prohibition on illegitimate means of seizing or retaining power, such as coups. This hierarchy of values raised the strong suspicion that Africa’s incumbents had just found a more sophisticated way of protecting themselves against usurpers. And many of them continued to behave in the sort of undemocratic and unconstitutional fashion that often triggered coups and rebellions – or mass protests, as was the case in Egypt and Burkina Faso.

But, as Dersso pointed out, the 2007 Charter on Democracy, Elections and Governance also contains a clause which says that tampering with the constitution in a way that thwarts the will of the people – for instance, by removing limits on presidential terms – can also be construed as unconstitutional change of power. This clause is coming into sharp focus this year when 18 elections are scheduled to take place across Africa, 12 of which the AU considers very sensitive and where it is engaging in active quiet diplomacy to prevent instability, the AU Commissioner for Political Affairs, Aisha Abdullahi, said at the AU this week. In several of these polls and in some more elections next year, the trigger of instability is that incumbents are trying to amend their countries’ constitutionally enshrined terms limits, to remain in power. Burkina Faso was perhaps the prologue last year to a potentially explosive drama in several acts that looks set to unfold around the continent over this period. There President Blaise Compaoré, until then seemingly a member in good standing of Africa’s elite club of presidents-for-life, was unexpectedly toppled in a popular uprising sparked by his attempts to remove the two-term limit from the constitution (he had, of course, been in power much longer than two terms, but the constitution was more recent).

As Dersso pointed out, the AU hesitated over Burkina Faso. It did not condemn Compaoré’s tampering with the constitution as an infringement of the AU’s prohibition against unconstitutional change/maintenance of government. But it didn’t condemn the popular uprising as such either, thus implicitly acknowledging that Compaoré had tried to use legal and constitutional methods for an inherently undemocratic and unconstitutional purpose. Stephanie Wolters, Head of the ISS Conflict Prevention and Risk Analysis Division, described how similar attempts to remove constitutional term limits in the two Congos and in Burundi are also provoking instability and distracting these countries from attending to major problems. In Burundi, President Pierre Nkurunziza is trying to stand for a third term this year, and in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and Republic of Congo, Joseph Kabila and Dénis Sassou Nguesso are respectively hoping to do so, despite official denials, in 2016. In the Republic of Congo’s 2002 constitution the two-term limit is completely entrenched, and so Wolters said Sassou Nguesso and his ruling party were now trying to change the entire constitution, arguing that it was a post-conflict compromise document, which does not answer to today’s demands. Across the Congo River a similar drama is playing out. Wolters said it was pretty obvious to everyone that Kabila wants to run for a third term next year, though, like Sassou Nguesso, he has not publicly said so. The DRC constitution also entrenches a two-term limit though, and Wolters said Kabila’s aides have already begun to insinuate into the public discourse that the constitution should be replaced entirely to adjust to modern realities.

In all three countries, though, the people – mostly young – are fighting back, dismayed and infuriated by what they rightly see as efforts by their leaders to drag them back to old Africa, which all of their countries have fought so hard to escape over the last decade or so. Opposition political parties and civil society are joining forces to mount courageous protests, as they did in Burkina Faso. The governments are hitting back, arresting opposition leaders on trumped up charges and violently suppressing street protests as Kabila’s forces did this month, evidently killing scores of them. Wolters said these attempts of the leaders to cling to power were destabilising the countries and focusing all their political energies on this one issue, neglecting the business of running the state. Yet the people are also registering important victories for democracy. In Burundi, Parliament defeated Nkurunziza’s draft bill to amend the constitution, by one vote, though Wolters said she was sure he would find another way to stay in power. In the DRC last week, Parliament finally withdrew a government bill that would have postponed elections until after a new census had been conducted. This was seen by the opposition as a ruse to keep Kabila in power indefinitely as properly counting all of Congo’s people would have taken years. Is the AU helping the people to resist these efforts by die-hard incumbents to cling to power at all costs? Indirectly, at least, yes. As Dersso pointed out, the opponents of Compaoré’s attempt to amend the constitution were inspired by that clause in the Charter on Democracy, Election, and Governance, which deems tampering with the constitution to cling to power a form of unconstitutional change of government.

It would also seem the African street is inspired by a concomitant shift in the AU’s attitude towards popular uprisings, though it is still wrestling with the concept. When it drew up the draft list of crimes that the African Court could prosecute, it originally included unconstitutional changes of government but with an exception – inspired by the Arab Spring – for popular uprisings against oppressive, undemocratic governments. So it did not condemn the popular uprising that toppled Egypt’s long-time president Hosni Mubarak in 2011, and distinguished that from the forced removal of Mohammed Morsi in 2012, which it defined as a coup. Dersso said the AU had also learnt lessons from Burkina Faso, and so was engaging in more energetic preventative diplomacy in other countries, like Togo, where incumbents are also clinging to power – as Commissioner Abdullahi suggested. So maybe that’s evolution: though clearly the AU should be much more upfront and proactive in jumping on and publicly condemning any efforts to change constitutions to cling to power. And what message will it sending this week by electing the continent’s third-longest-serving and, at 90, certainly the oldest, leader, President Robert Mugabe as its chairperson for 2015? AU Commission Deputy Chair, Erastus Mwencha, defended the decision this week, saying it was democratic because the AU chooses its leaders on a regional rotation system, and Mugabe is the Southern African Development Community’s nominee. The AU has declined such nominees before, though – or at least one, Sudan’s Omar al-Bashir. The real reason that it won’t decline Mugabe, though, as one South African official admitted is that because he is the West’s pariah, he is Africa’s hero. Africa is evolving politically. But for now, at least, the background music of colonialism is still drowning out the foreground music of democracy.

Culled from DefenceWeb

- Details

- Ngwa Bertrand

- Hits: 1936

- Details

- Editorial

Is Africa slowly turning the rhetoric of democracy into action? The Constitutive Act of the African Union (AU), which introduced to the continental body the values of democracy, rule of law and constitutionalism, is 13 years old. And its prohibition of seizing power unconstitutionally goes back even earlier to 2000, preceding the AU.

But the AU created a two-tier ranking of values, as Solomon Ayele Dersso, Head of the Peace and Security Council (PSC) programme at the Institute of Security Studies (ISS), pointed out at a seminar in Addis Ababa this week. The AU implicitly ranked the prohibition against unconstitutional changes of government as a higher value by enforcing it with the sanction of suspension from membership of the AU. It attached no sanction at all to undemocratic, illegal and unconstitutional behaviour more generally. The ban on unconstitutional changes of government was almost entirely interpreted as a prohibition on illegitimate means of seizing or retaining power, such as coups. This hierarchy of values raised the strong suspicion that Africa’s incumbents had just found a more sophisticated way of protecting themselves against usurpers. And many of them continued to behave in the sort of undemocratic and unconstitutional fashion that often triggered coups and rebellions – or mass protests, as was the case in Egypt and Burkina Faso.

But, as Dersso pointed out, the 2007 Charter on Democracy, Elections and Governance also contains a clause which says that tampering with the constitution in a way that thwarts the will of the people – for instance, by removing limits on presidential terms – can also be construed as unconstitutional change of power. This clause is coming into sharp focus this year when 18 elections are scheduled to take place across Africa, 12 of which the AU considers very sensitive and where it is engaging in active quiet diplomacy to prevent instability, the AU Commissioner for Political Affairs, Aisha Abdullahi, said at the AU this week. In several of these polls and in some more elections next year, the trigger of instability is that incumbents are trying to amend their countries’ constitutionally enshrined terms limits, to remain in power. Burkina Faso was perhaps the prologue last year to a potentially explosive drama in several acts that looks set to unfold around the continent over this period. There President Blaise Compaoré, until then seemingly a member in good standing of Africa’s elite club of presidents-for-life, was unexpectedly toppled in a popular uprising sparked by his attempts to remove the two-term limit from the constitution (he had, of course, been in power much longer than two terms, but the constitution was more recent).

As Dersso pointed out, the AU hesitated over Burkina Faso. It did not condemn Compaoré’s tampering with the constitution as an infringement of the AU’s prohibition against unconstitutional change/maintenance of government. But it didn’t condemn the popular uprising as such either, thus implicitly acknowledging that Compaoré had tried to use legal and constitutional methods for an inherently undemocratic and unconstitutional purpose. Stephanie Wolters, Head of the ISS Conflict Prevention and Risk Analysis Division, described how similar attempts to remove constitutional term limits in the two Congos and in Burundi are also provoking instability and distracting these countries from attending to major problems. In Burundi, President Pierre Nkurunziza is trying to stand for a third term this year, and in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and Republic of Congo, Joseph Kabila and Dénis Sassou Nguesso are respectively hoping to do so, despite official denials, in 2016. In the Republic of Congo’s 2002 constitution the two-term limit is completely entrenched, and so Wolters said Sassou Nguesso and his ruling party were now trying to change the entire constitution, arguing that it was a post-conflict compromise document, which does not answer to today’s demands. Across the Congo River a similar drama is playing out. Wolters said it was pretty obvious to everyone that Kabila wants to run for a third term next year, though, like Sassou Nguesso, he has not publicly said so. The DRC constitution also entrenches a two-term limit though, and Wolters said Kabila’s aides have already begun to insinuate into the public discourse that the constitution should be replaced entirely to adjust to modern realities.

In all three countries, though, the people – mostly young – are fighting back, dismayed and infuriated by what they rightly see as efforts by their leaders to drag them back to old Africa, which all of their countries have fought so hard to escape over the last decade or so. Opposition political parties and civil society are joining forces to mount courageous protests, as they did in Burkina Faso. The governments are hitting back, arresting opposition leaders on trumped up charges and violently suppressing street protests as Kabila’s forces did this month, evidently killing scores of them. Wolters said these attempts of the leaders to cling to power were destabilising the countries and focusing all their political energies on this one issue, neglecting the business of running the state. Yet the people are also registering important victories for democracy. In Burundi, Parliament defeated Nkurunziza’s draft bill to amend the constitution, by one vote, though Wolters said she was sure he would find another way to stay in power. In the DRC last week, Parliament finally withdrew a government bill that would have postponed elections until after a new census had been conducted. This was seen by the opposition as a ruse to keep Kabila in power indefinitely as properly counting all of Congo’s people would have taken years. Is the AU helping the people to resist these efforts by die-hard incumbents to cling to power at all costs? Indirectly, at least, yes. As Dersso pointed out, the opponents of Compaoré’s attempt to amend the constitution were inspired by that clause in the Charter on Democracy, Election, and Governance, which deems tampering with the constitution to cling to power a form of unconstitutional change of government.

It would also seem the African street is inspired by a concomitant shift in the AU’s attitude towards popular uprisings, though it is still wrestling with the concept. When it drew up the draft list of crimes that the African Court could prosecute, it originally included unconstitutional changes of government but with an exception – inspired by the Arab Spring – for popular uprisings against oppressive, undemocratic governments. So it did not condemn the popular uprising that toppled Egypt’s long-time president Hosni Mubarak in 2011, and distinguished that from the forced removal of Mohammed Morsi in 2012, which it defined as a coup. Dersso said the AU had also learnt lessons from Burkina Faso, and so was engaging in more energetic preventative diplomacy in other countries, like Togo, where incumbents are also clinging to power – as Commissioner Abdullahi suggested. So maybe that’s evolution: though clearly the AU should be much more upfront and proactive in jumping on and publicly condemning any efforts to change constitutions to cling to power. And what message will it sending this week by electing the continent’s third-longest-serving and, at 90, certainly the oldest, leader, President Robert Mugabe as its chairperson for 2015? AU Commission Deputy Chair, Erastus Mwencha, defended the decision this week, saying it was democratic because the AU chooses its leaders on a regional rotation system, and Mugabe is the Southern African Development Community’s nominee. The AU has declined such nominees before, though – or at least one, Sudan’s Omar al-Bashir. The real reason that it won’t decline Mugabe, though, as one South African official admitted is that because he is the West’s pariah, he is Africa’s hero. Africa is evolving politically. But for now, at least, the background music of colonialism is still drowning out the foreground music of democracy.

Culled from DefenceWeb

- Details

- Ngwa Bertrand

- Hits: 1529

- Details

- Editorial

Is Africa slowly turning the rhetoric of democracy into action? The Constitutive Act of the African Union (AU), which introduced to the continental body the values of democracy, rule of law and constitutionalism, is 13 years old. And its prohibition of seizing power unconstitutionally goes back even earlier to 2000, preceding the AU.

But the AU created a two-tier ranking of values, as Solomon Ayele Dersso, Head of the Peace and Security Council (PSC) programme at the Institute of Security Studies (ISS), pointed out at a seminar in Addis Ababa this week. The AU implicitly ranked the prohibition against unconstitutional changes of government as a higher value by enforcing it with the sanction of suspension from membership of the AU. It attached no sanction at all to undemocratic, illegal and unconstitutional behaviour more generally. The ban on unconstitutional changes of government was almost entirely interpreted as a prohibition on illegitimate means of seizing or retaining power, such as coups. This hierarchy of values raised the strong suspicion that Africa’s incumbents had just found a more sophisticated way of protecting themselves against usurpers. And many of them continued to behave in the sort of undemocratic and unconstitutional fashion that often triggered coups and rebellions – or mass protests, as was the case in Egypt and Burkina Faso.

But, as Dersso pointed out, the 2007 Charter on Democracy, Elections and Governance also contains a clause which says that tampering with the constitution in a way that thwarts the will of the people – for instance, by removing limits on presidential terms – can also be construed as unconstitutional change of power. This clause is coming into sharp focus this year when 18 elections are scheduled to take place across Africa, 12 of which the AU considers very sensitive and where it is engaging in active quiet diplomacy to prevent instability, the AU Commissioner for Political Affairs, Aisha Abdullahi, said at the AU this week. In several of these polls and in some more elections next year, the trigger of instability is that incumbents are trying to amend their countries’ constitutionally enshrined terms limits, to remain in power. Burkina Faso was perhaps the prologue last year to a potentially explosive drama in several acts that looks set to unfold around the continent over this period. There President Blaise Compaoré, until then seemingly a member in good standing of Africa’s elite club of presidents-for-life, was unexpectedly toppled in a popular uprising sparked by his attempts to remove the two-term limit from the constitution (he had, of course, been in power much longer than two terms, but the constitution was more recent).

As Dersso pointed out, the AU hesitated over Burkina Faso. It did not condemn Compaoré’s tampering with the constitution as an infringement of the AU’s prohibition against unconstitutional change/maintenance of government. But it didn’t condemn the popular uprising as such either, thus implicitly acknowledging that Compaoré had tried to use legal and constitutional methods for an inherently undemocratic and unconstitutional purpose. Stephanie Wolters, Head of the ISS Conflict Prevention and Risk Analysis Division, described how similar attempts to remove constitutional term limits in the two Congos and in Burundi are also provoking instability and distracting these countries from attending to major problems. In Burundi, President Pierre Nkurunziza is trying to stand for a third term this year, and in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and Republic of Congo, Joseph Kabila and Dénis Sassou Nguesso are respectively hoping to do so, despite official denials, in 2016. In the Republic of Congo’s 2002 constitution the two-term limit is completely entrenched, and so Wolters said Sassou Nguesso and his ruling party were now trying to change the entire constitution, arguing that it was a post-conflict compromise document, which does not answer to today’s demands. Across the Congo River a similar drama is playing out. Wolters said it was pretty obvious to everyone that Kabila wants to run for a third term next year, though, like Sassou Nguesso, he has not publicly said so. The DRC constitution also entrenches a two-term limit though, and Wolters said Kabila’s aides have already begun to insinuate into the public discourse that the constitution should be replaced entirely to adjust to modern realities.

In all three countries, though, the people – mostly young – are fighting back, dismayed and infuriated by what they rightly see as efforts by their leaders to drag them back to old Africa, which all of their countries have fought so hard to escape over the last decade or so. Opposition political parties and civil society are joining forces to mount courageous protests, as they did in Burkina Faso. The governments are hitting back, arresting opposition leaders on trumped up charges and violently suppressing street protests as Kabila’s forces did this month, evidently killing scores of them. Wolters said these attempts of the leaders to cling to power were destabilising the countries and focusing all their political energies on this one issue, neglecting the business of running the state. Yet the people are also registering important victories for democracy. In Burundi, Parliament defeated Nkurunziza’s draft bill to amend the constitution, by one vote, though Wolters said she was sure he would find another way to stay in power. In the DRC last week, Parliament finally withdrew a government bill that would have postponed elections until after a new census had been conducted. This was seen by the opposition as a ruse to keep Kabila in power indefinitely as properly counting all of Congo’s people would have taken years. Is the AU helping the people to resist these efforts by die-hard incumbents to cling to power at all costs? Indirectly, at least, yes. As Dersso pointed out, the opponents of Compaoré’s attempt to amend the constitution were inspired by that clause in the Charter on Democracy, Election, and Governance, which deems tampering with the constitution to cling to power a form of unconstitutional change of government.

It would also seem the African street is inspired by a concomitant shift in the AU’s attitude towards popular uprisings, though it is still wrestling with the concept. When it drew up the draft list of crimes that the African Court could prosecute, it originally included unconstitutional changes of government but with an exception – inspired by the Arab Spring – for popular uprisings against oppressive, undemocratic governments. So it did not condemn the popular uprising that toppled Egypt’s long-time president Hosni Mubarak in 2011, and distinguished that from the forced removal of Mohammed Morsi in 2012, which it defined as a coup. Dersso said the AU had also learnt lessons from Burkina Faso, and so was engaging in more energetic preventative diplomacy in other countries, like Togo, where incumbents are also clinging to power – as Commissioner Abdullahi suggested. So maybe that’s evolution: though clearly the AU should be much more upfront and proactive in jumping on and publicly condemning any efforts to change constitutions to cling to power. And what message will it sending this week by electing the continent’s third-longest-serving and, at 90, certainly the oldest, leader, President Robert Mugabe as its chairperson for 2015? AU Commission Deputy Chair, Erastus Mwencha, defended the decision this week, saying it was democratic because the AU chooses its leaders on a regional rotation system, and Mugabe is the Southern African Development Community’s nominee. The AU has declined such nominees before, though – or at least one, Sudan’s Omar al-Bashir. The real reason that it won’t decline Mugabe, though, as one South African official admitted is that because he is the West’s pariah, he is Africa’s hero. Africa is evolving politically. But for now, at least, the background music of colonialism is still drowning out the foreground music of democracy.

Culled from DefenceWeb

- Details

- Ngwa Bertrand

- Hits: 1366

- Details

- Editorial

Is Africa slowly turning the rhetoric of democracy into action? The Constitutive Act of the African Union (AU), which introduced to the continental body the values of democracy, rule of law and constitutionalism, is 13 years old. And its prohibition of seizing power unconstitutionally goes back even earlier to 2000, preceding the AU.

But the AU created a two-tier ranking of values, as Solomon Ayele Dersso, Head of the Peace and Security Council (PSC) programme at the Institute of Security Studies (ISS), pointed out at a seminar in Addis Ababa this week. The AU implicitly ranked the prohibition against unconstitutional changes of government as a higher value by enforcing it with the sanction of suspension from membership of the AU. It attached no sanction at all to undemocratic, illegal and unconstitutional behaviour more generally. The ban on unconstitutional changes of government was almost entirely interpreted as a prohibition on illegitimate means of seizing or retaining power, such as coups. This hierarchy of values raised the strong suspicion that Africa’s incumbents had just found a more sophisticated way of protecting themselves against usurpers. And many of them continued to behave in the sort of undemocratic and unconstitutional fashion that often triggered coups and rebellions – or mass protests, as was the case in Egypt and Burkina Faso.

But, as Dersso pointed out, the 2007 Charter on Democracy, Elections and Governance also contains a clause which says that tampering with the constitution in a way that thwarts the will of the people – for instance, by removing limits on presidential terms – can also be construed as unconstitutional change of power. This clause is coming into sharp focus this year when 18 elections are scheduled to take place across Africa, 12 of which the AU considers very sensitive and where it is engaging in active quiet diplomacy to prevent instability, the AU Commissioner for Political Affairs, Aisha Abdullahi, said at the AU this week. In several of these polls and in some more elections next year, the trigger of instability is that incumbents are trying to amend their countries’ constitutionally enshrined terms limits, to remain in power. Burkina Faso was perhaps the prologue last year to a potentially explosive drama in several acts that looks set to unfold around the continent over this period. There President Blaise Compaoré, until then seemingly a member in good standing of Africa’s elite club of presidents-for-life, was unexpectedly toppled in a popular uprising sparked by his attempts to remove the two-term limit from the constitution (he had, of course, been in power much longer than two terms, but the constitution was more recent).

As Dersso pointed out, the AU hesitated over Burkina Faso. It did not condemn Compaoré’s tampering with the constitution as an infringement of the AU’s prohibition against unconstitutional change/maintenance of government. But it didn’t condemn the popular uprising as such either, thus implicitly acknowledging that Compaoré had tried to use legal and constitutional methods for an inherently undemocratic and unconstitutional purpose. Stephanie Wolters, Head of the ISS Conflict Prevention and Risk Analysis Division, described how similar attempts to remove constitutional term limits in the two Congos and in Burundi are also provoking instability and distracting these countries from attending to major problems. In Burundi, President Pierre Nkurunziza is trying to stand for a third term this year, and in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and Republic of Congo, Joseph Kabila and Dénis Sassou Nguesso are respectively hoping to do so, despite official denials, in 2016. In the Republic of Congo’s 2002 constitution the two-term limit is completely entrenched, and so Wolters said Sassou Nguesso and his ruling party were now trying to change the entire constitution, arguing that it was a post-conflict compromise document, which does not answer to today’s demands. Across the Congo River a similar drama is playing out. Wolters said it was pretty obvious to everyone that Kabila wants to run for a third term next year, though, like Sassou Nguesso, he has not publicly said so. The DRC constitution also entrenches a two-term limit though, and Wolters said Kabila’s aides have already begun to insinuate into the public discourse that the constitution should be replaced entirely to adjust to modern realities.

In all three countries, though, the people – mostly young – are fighting back, dismayed and infuriated by what they rightly see as efforts by their leaders to drag them back to old Africa, which all of their countries have fought so hard to escape over the last decade or so. Opposition political parties and civil society are joining forces to mount courageous protests, as they did in Burkina Faso. The governments are hitting back, arresting opposition leaders on trumped up charges and violently suppressing street protests as Kabila’s forces did this month, evidently killing scores of them. Wolters said these attempts of the leaders to cling to power were destabilising the countries and focusing all their political energies on this one issue, neglecting the business of running the state. Yet the people are also registering important victories for democracy. In Burundi, Parliament defeated Nkurunziza’s draft bill to amend the constitution, by one vote, though Wolters said she was sure he would find another way to stay in power. In the DRC last week, Parliament finally withdrew a government bill that would have postponed elections until after a new census had been conducted. This was seen by the opposition as a ruse to keep Kabila in power indefinitely as properly counting all of Congo’s people would have taken years. Is the AU helping the people to resist these efforts by die-hard incumbents to cling to power at all costs? Indirectly, at least, yes. As Dersso pointed out, the opponents of Compaoré’s attempt to amend the constitution were inspired by that clause in the Charter on Democracy, Election, and Governance, which deems tampering with the constitution to cling to power a form of unconstitutional change of government.

It would also seem the African street is inspired by a concomitant shift in the AU’s attitude towards popular uprisings, though it is still wrestling with the concept. When it drew up the draft list of crimes that the African Court could prosecute, it originally included unconstitutional changes of government but with an exception – inspired by the Arab Spring – for popular uprisings against oppressive, undemocratic governments. So it did not condemn the popular uprising that toppled Egypt’s long-time president Hosni Mubarak in 2011, and distinguished that from the forced removal of Mohammed Morsi in 2012, which it defined as a coup. Dersso said the AU had also learnt lessons from Burkina Faso, and so was engaging in more energetic preventative diplomacy in other countries, like Togo, where incumbents are also clinging to power – as Commissioner Abdullahi suggested. So maybe that’s evolution: though clearly the AU should be much more upfront and proactive in jumping on and publicly condemning any efforts to change constitutions to cling to power. And what message will it sending this week by electing the continent’s third-longest-serving and, at 90, certainly the oldest, leader, President Robert Mugabe as its chairperson for 2015? AU Commission Deputy Chair, Erastus Mwencha, defended the decision this week, saying it was democratic because the AU chooses its leaders on a regional rotation system, and Mugabe is the Southern African Development Community’s nominee. The AU has declined such nominees before, though – or at least one, Sudan’s Omar al-Bashir. The real reason that it won’t decline Mugabe, though, as one South African official admitted is that because he is the West’s pariah, he is Africa’s hero. Africa is evolving politically. But for now, at least, the background music of colonialism is still drowning out the foreground music of democracy.

Culled from DefenceWeb

- Details

- Ngwa Bertrand

- Hits: 1488

- Details

- Editorial

Is Africa slowly turning the rhetoric of democracy into action? The Constitutive Act of the African Union (AU), which introduced to the continental body the values of democracy, rule of law and constitutionalism, is 13 years old. And its prohibition of seizing power unconstitutionally goes back even earlier to 2000, preceding the AU.

But the AU created a two-tier ranking of values, as Solomon Ayele Dersso, Head of the Peace and Security Council (PSC) programme at the Institute of Security Studies (ISS), pointed out at a seminar in Addis Ababa this week. The AU implicitly ranked the prohibition against unconstitutional changes of government as a higher value by enforcing it with the sanction of suspension from membership of the AU. It attached no sanction at all to undemocratic, illegal and unconstitutional behaviour more generally. The ban on unconstitutional changes of government was almost entirely interpreted as a prohibition on illegitimate means of seizing or retaining power, such as coups. This hierarchy of values raised the strong suspicion that Africa’s incumbents had just found a more sophisticated way of protecting themselves against usurpers. And many of them continued to behave in the sort of undemocratic and unconstitutional fashion that often triggered coups and rebellions – or mass protests, as was the case in Egypt and Burkina Faso.

But, as Dersso pointed out, the 2007 Charter on Democracy, Elections and Governance also contains a clause which says that tampering with the constitution in a way that thwarts the will of the people – for instance, by removing limits on presidential terms – can also be construed as unconstitutional change of power. This clause is coming into sharp focus this year when 18 elections are scheduled to take place across Africa, 12 of which the AU considers very sensitive and where it is engaging in active quiet diplomacy to prevent instability, the AU Commissioner for Political Affairs, Aisha Abdullahi, said at the AU this week. In several of these polls and in some more elections next year, the trigger of instability is that incumbents are trying to amend their countries’ constitutionally enshrined terms limits, to remain in power. Burkina Faso was perhaps the prologue last year to a potentially explosive drama in several acts that looks set to unfold around the continent over this period. There President Blaise Compaoré, until then seemingly a member in good standing of Africa’s elite club of presidents-for-life, was unexpectedly toppled in a popular uprising sparked by his attempts to remove the two-term limit from the constitution (he had, of course, been in power much longer than two terms, but the constitution was more recent).

As Dersso pointed out, the AU hesitated over Burkina Faso. It did not condemn Compaoré’s tampering with the constitution as an infringement of the AU’s prohibition against unconstitutional change/maintenance of government. But it didn’t condemn the popular uprising as such either, thus implicitly acknowledging that Compaoré had tried to use legal and constitutional methods for an inherently undemocratic and unconstitutional purpose. Stephanie Wolters, Head of the ISS Conflict Prevention and Risk Analysis Division, described how similar attempts to remove constitutional term limits in the two Congos and in Burundi are also provoking instability and distracting these countries from attending to major problems. In Burundi, President Pierre Nkurunziza is trying to stand for a third term this year, and in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and Republic of Congo, Joseph Kabila and Dénis Sassou Nguesso are respectively hoping to do so, despite official denials, in 2016. In the Republic of Congo’s 2002 constitution the two-term limit is completely entrenched, and so Wolters said Sassou Nguesso and his ruling party were now trying to change the entire constitution, arguing that it was a post-conflict compromise document, which does not answer to today’s demands. Across the Congo River a similar drama is playing out. Wolters said it was pretty obvious to everyone that Kabila wants to run for a third term next year, though, like Sassou Nguesso, he has not publicly said so. The DRC constitution also entrenches a two-term limit though, and Wolters said Kabila’s aides have already begun to insinuate into the public discourse that the constitution should be replaced entirely to adjust to modern realities.

In all three countries, though, the people – mostly young – are fighting back, dismayed and infuriated by what they rightly see as efforts by their leaders to drag them back to old Africa, which all of their countries have fought so hard to escape over the last decade or so. Opposition political parties and civil society are joining forces to mount courageous protests, as they did in Burkina Faso. The governments are hitting back, arresting opposition leaders on trumped up charges and violently suppressing street protests as Kabila’s forces did this month, evidently killing scores of them. Wolters said these attempts of the leaders to cling to power were destabilising the countries and focusing all their political energies on this one issue, neglecting the business of running the state. Yet the people are also registering important victories for democracy. In Burundi, Parliament defeated Nkurunziza’s draft bill to amend the constitution, by one vote, though Wolters said she was sure he would find another way to stay in power. In the DRC last week, Parliament finally withdrew a government bill that would have postponed elections until after a new census had been conducted. This was seen by the opposition as a ruse to keep Kabila in power indefinitely as properly counting all of Congo’s people would have taken years. Is the AU helping the people to resist these efforts by die-hard incumbents to cling to power at all costs? Indirectly, at least, yes. As Dersso pointed out, the opponents of Compaoré’s attempt to amend the constitution were inspired by that clause in the Charter on Democracy, Election, and Governance, which deems tampering with the constitution to cling to power a form of unconstitutional change of government.

It would also seem the African street is inspired by a concomitant shift in the AU’s attitude towards popular uprisings, though it is still wrestling with the concept. When it drew up the draft list of crimes that the African Court could prosecute, it originally included unconstitutional changes of government but with an exception – inspired by the Arab Spring – for popular uprisings against oppressive, undemocratic governments. So it did not condemn the popular uprising that toppled Egypt’s long-time president Hosni Mubarak in 2011, and distinguished that from the forced removal of Mohammed Morsi in 2012, which it defined as a coup. Dersso said the AU had also learnt lessons from Burkina Faso, and so was engaging in more energetic preventative diplomacy in other countries, like Togo, where incumbents are also clinging to power – as Commissioner Abdullahi suggested. So maybe that’s evolution: though clearly the AU should be much more upfront and proactive in jumping on and publicly condemning any efforts to change constitutions to cling to power. And what message will it sending this week by electing the continent’s third-longest-serving and, at 90, certainly the oldest, leader, President Robert Mugabe as its chairperson for 2015? AU Commission Deputy Chair, Erastus Mwencha, defended the decision this week, saying it was democratic because the AU chooses its leaders on a regional rotation system, and Mugabe is the Southern African Development Community’s nominee. The AU has declined such nominees before, though – or at least one, Sudan’s Omar al-Bashir. The real reason that it won’t decline Mugabe, though, as one South African official admitted is that because he is the West’s pariah, he is Africa’s hero. Africa is evolving politically. But for now, at least, the background music of colonialism is still drowning out the foreground music of democracy.

Culled from DefenceWeb

- Details

- Ngwa Bertrand

- Hits: 1277

Local News

- Details

- Society

Kribi II: Man Caught Allegedly Abusing Child

- News Team

- 14.Sep.2025

- Details

- Society

Back to School 2025/2026 – Spotlight on Bamenda & Nkambe

- News Team

- 08.Sep.2025

- Details

- Society

Cameroon 2025: From Kamto to Biya: Longue Longue’s political flip shocks supporters

- News Team

- 08.Sep.2025

- Details

- Society

Meiganga bus crash spotlights Cameroon’s road safety crisis

- News Team

- 05.Sep.2025

EditorialView all

- Details

- Editorial

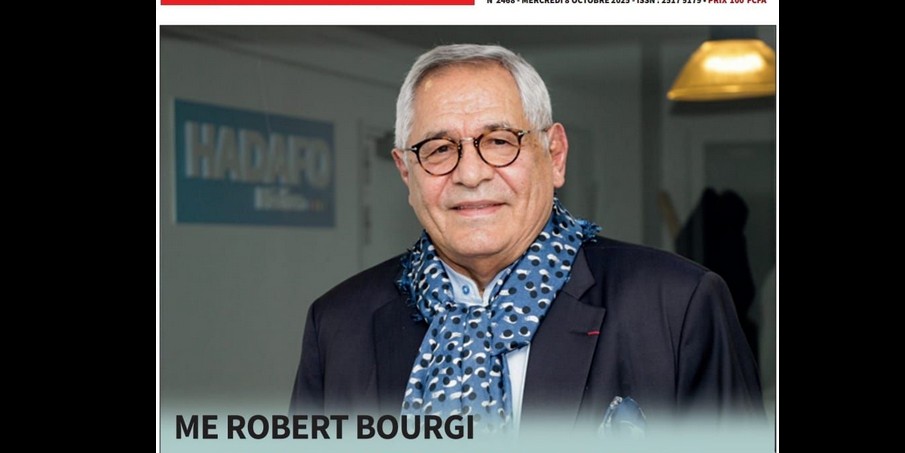

Robert Bourgi Turns on Paul Biya, Declares Him a Political Corpse

- News Team

- 10.Oct.2025

- Details

- Editorial

Heat in Maroua: What Biya’s Return Really Signals

- News Team

- 08.Oct.2025

- Details

- Editorial

Issa Tchiroma: Charles Mambo’s “Change Candidate” for Cameroon

- News Team

- 11.Sep.2025

- Details

- Editorial