Health

By Joachim Arrey in West Africa

The Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) is continuing its onward march to other African countries with very little resistance as many Sub-Saharan African countries are ill-equipped to handle such health emergencies. Many experts had thought it would be limited to West Africa, but a few days ago, the insidious and merciless killer showed up on Congolese shores uninvited and in a different form. This new strain is as dangerous as its West African cousin that has claimed more than 2,000 lives and sickened thousands of people. While WHO and other agencies put the number of deaths at less than 2,000, many experts argue that those figures are understated as in countries like Sierra Leone and Liberia, there are many shadow zones where many Ebola victims are not reported and family members sometimes prefer to keep their loved ones at home for them to die in the arms of their loved ones rather than take them to quarantine centres, an act that has helped the virus to spread like wild fire in traditional and impoverished African communities.

While love is critical during tough times, it is preposterous to insist on caring for infected loved ones, especially as typical traditional African settings are completely bereft of the proper scientific knowledge that can help members of the community deal with such a testing and tough health challenge that Ebola has thrown up on the continent. Those who have dared to toy with Ebola have not had the opportunity to tell their story. It is an experience nobody would even wish it on their worst enemy. In many cases, it has simply deleted whole families from the face of the earth. It has also dealt a severe blow to health communities in West African countries which were already in great need of well-trained health workers and state-of-the-art infrastructure before the virus reared its ugly head on their shores. Now that it is finally around and resisting all attempts to roll it back, these countries might be pushed further into the abyss of desperation as many health workers will surely quit their jobs and look to Western countries where salaries are better and sudden death is a remote reality.

With fragile health infrastructure and outdated traditional habits, it is increasingly becoming clear that Africa has a tough challenge on its hands. While the cause of the virus is still unclear, scientists however consider wild animals, which are a major source of proteins to many Sub-Saharan Africans, as the major vector in the spread of this virus that has no regard for social class or political status. With the sub-region mired in severe economic and financial times, many are seeking to know if Africa will be able to handle such a tough challenge, especially as life on the continent is not science-based and traditional ways are resisting news and innovative lifestyles that can help keep such a virus in check.

In many parts of the continent, it is normal to see a bunch of young men chasing a small rat in broad day light just because they believe that its rightful place is in their stomachs. Many hardly pause to think that such a small animal could spell death for many members of their community. While other continents such as North America and Europe have walked away from the consumption of these animals, in Africa their consumption has reduced them to endangered species. This is not the first time Ebola is striking the continent, but after every attack, Africans relapse to their old ways of hunting these animals for food and in the process shooting themselves in the foot. There are alternative protein sources which are risk-free and Africans stand to gain if they embrace those alternative sources. There are surely new ways that can stop the African from shedding tears of sorrow. While hunting animals for food is their way of life, they must also understand that every way of life can be changed. They simply have to take a look at what others are doing to stay away from pain and suffering. These viruses are a nightmare. They have blighted life on the continent. Each time they show up in one country, they destabilize the entire continent. Isn’t it time to learn?

On the economic front, business is almost at a standstill in many parts of the continent. The continent’s aviation and tourism industries have taken a hit. Many businessmen are already under pressure as their businesses take a nosedive due to the threat posed by Ebola. While human life is more important, it must be pointed out that the virus has rolled back the continent by at least ten years in terms of business. And this fight has just been playing out in a few weeks and WHO experts indicate that the fight against Ebola might take more than six months. With no end in sight, it is clear that Africa is walking into tough economic times. At the end of the battle, it will be hard to really count the economic cost as many businesses will be a thing of the past. African governments are cash-strapped and with a lot on their plates, they will not be able to help those businesses affected by this dangerous virus to stand on their feet. Ebola does not only kill humans. It also kills businesses and this makes the future really bleak for many young Africans who may not find work. This could translate into more future political and economic challenges to a continent that is permanently in the throes of political chaos. That is why many experts are asking if Africa will be able to handle the mess left behind by Ebola.

- Details

- Ngwa Bertrand

- Hits: 2483

A Royal Air Force plane carrying a British citizen who contracted the deadly Ebola virus in Sierra Leone took off from the airport in the capital Freetown on Sunday bound for Britain, a Reuters witness said.

The Briton, believed to be a medical volunteer who had been working at an Ebola treatment site in the West African country, was brought by ambulance to the grey Boeing C-17 cargo plane.

The person is believed to be the first Briton to fall victim to the deadly disease that has spread across the West African region since March, the Department of Health said on Saturday.

The World Health Organization estimates that the current Ebola epidemic--the world's worst ever with 1,427 documented deaths--will likely take six to nine months to halt.

- Details

- Ngwa Bertrand

- Hits: 2479

Authorities in the Democratic Republic of Congo say they have found two cases of Ebola in the country's north-west.

They are the first reported cases outside West Africa since the outbreak there began, although it is not clear if the cases are directly linked to that outbreak.

So far 1,427 people have died from the virus.

The speed and extent of the outbreak has been "unprecedented", the World Health Organization (WHO) says.

The number of current cases in West Africa now stands at 2,615.

Several people had been reported killed in the past month by an unidentified fever in the Equateur region of the Democratic Republic of Congo.

On Sunday, health minister Felix Kabange Numbi said eight of the fever victims had been tested for Ebola.

"The results are positive. The Ebola virus is confirmed in DRC," Mr Numbi told the Agence France-Presse news agency.

- Details

- Ngwa Bertrand

- Hits: 2392

Nigerian officials confirmed two new cases of Ebola on Friday, bringing the number of people who have been stricken with the disease in Africa’s most populous nation to 14. Five have died, five have recovered and four are in isolation and being treated.

Onyebuchi Chukwu, Nigeria’s health minister, said the two new cases are the spouses of medical workers — a man and a woman — who took care of Patrick Sawyer, the Liberian American who brought Ebola to Nigeria in July. Sawyer was hospitalized on arrival in the Lagos airport from Liberia but was not immediately quarantined. He later died.

Even with the new cases, Nigeria has been more successful than some other West African countries in containing the outbreak, thanks to rigorous monitoring and contact tracing. “We have been able to close down the epidemic, control it, and we are not letting down our guard,” Chukwu said in a telephone interview.

The new patients, who were under surveillance for 15 days before displaying symptoms, are the first cases involving people who didn’t have direct contact with Sawyer.

A total of 213 people in Nigeria are being closely watched for any signs of the disease. They are confined to their homes and subject to daily checkups from health teams. Their families have been briefed extensively on how to recognize symptoms and avoid transmission.

Sixty-seven people who were under surveillance have undergone the 21-day waiting period and been cleared as disease-free.

The outbreak has mostly been confined to Lagos, a city of 21 million people. A nurse who treated Sawyer fled surveillance in Lagos to be with her husband in southeastern Enugu state; now six people with whom she had contact are under surveillance as well. The nurse is one of four people currently in isolation in Lagos.

Nigeria’s outbreak stoked fears that Ebola could be spread by air travel. Major carriers, including British Airways and Emirates, canceled flights to and from Liberia and Sierra Leone, the countries with the most Ebola cases.

“The joke in Nigeria is, ‘Ebola isn’t airborne, but it came into Nigeria by air,’ ” said Chukwu, emphasizing that Nigeria was not closing its borders or restricting travel.

The World Health Organization advises against any ban on travel or trade, warning that restrictions will result in food and fuel shortages and undermine response efforts. Despite that, countries that serve as major travel hubs throughout the continent, including Senegal, Kenya and South Africa, have barred travelers from the countries hardest hit by the epidemic: Liberia, Sierra Leone and Guinea.

Nigeria is ramping up its monitoring of airline passengers to detect any with higher-than-normal temperatures and is requiring travelers to fill out questionnaires on the details of their trips.

“We’ve not closed borders, but we are actively screening,” Chukwu said. “People are happy with this — they know government is doing something to protect them.”

- Details

- Ngwa Bertrand

- Hits: 2657

Joachim Arrey in Abidjan, Cote d’Ivoire

Though Africa has always been in the spotlight for all the wrong reasons - poverty, HIV and wars – the continent is this time making news for the deadly viruses that are besieging it. Ebola has been claiming many lives in Liberia, Sierra Leone, Guinea and Nigeria, and the fear of this deadly virus can be seen on many faces across the continent. Ebola alone has engineered the death of more than a thousand people across the continent and due to the speed with which it claims its victims, it has caused many events such as conferences, seminars and workshops scheduled to take place on the continent to be cancelled. Trade is slowing down, as the free movement of goods and persons is being checked due to this invisible killer. Foreign investors are holding off on possible investments as Ebola’s presence on the continent is bad news to them. Africa has an image problem, but the presence of these viruses is casting the entire continent in very bad light.

But just when a silver lining has started to emerge from the continent’s the huge, dark cloud following the positive news about the effectiveness of the anti-Ebola drug; another destructive virus has reared its ugly head in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) where it has already claimed many lives. This no-name virus seems to be transforming Ebola into a child’s play. It should be underscored that Ebola started in Congo and its name is the name of a DRC village whence it started.

According to Congolese health ministry, the deadly hemorrhagic fever of unknown origin has rushed 13 people out of this planet in the northwestern DRC since breaking out on August 11. The country’s health ministry adds that all 13 casualties occurred after suffering from a fever, diarrhea, vomiting and, in a terminal stage, they vomit a black substance. Some 80 people who have come into contact with the deceased have been admitted to hospital.

The first victim was a pregnant woman and the 12 others -- including five medics -- died after coming into contact with her. About 80 people who had contact with the deceased are also currently under observation.

The DRC hemorrhagic fever has reduced Ebola to a dress rehearsal. These viruses seem to be conniving to shut down the entire continent. Ebola alone has already created huge problems to the continent's economy. The continent's tourism and aviation industries are fighting with their backs to the wall, as many airlines have shut down their operations to and from Ebola-affected countries. Tourism numbers to the continent have dropped sharply with many foreign tourists cancelling their trips to the naturally beautiful continent.

However, while the attacks from these viruses are no good news to the struggling continent, they however do offer some hope. Africans have to change their ways or they will make their continent home to these dangerous viruses. It sometimes takes a tragedy for a people to learn. Africans have to learn from these ugly situations. It cannot be business as usual. Many African countries have huge water and sanitation challenges despite efforts by development banks like the African Development Bank and the World Bank to help reverse some of these unfortunate situations.

The people’s culture also seems to be standing in the way to a better life. Africa’s social life, erroneously considered by Africans as the best in the world, is in part, to blame for the rapid spread of these viruses. Africans love shaking hands, eating and drinking from the same containers and even hugging each other many times in a day. It is normal to find huge numbers of African in the same place at the same time for no real reasons. And these viruses love such informal meeting spots where the rules of hygiene are not taken into consideration. In West African countries like Senegal and Mali, eating from the same plate is a common tradition. It is a sign of love, but it is unfortunately fraught with danger and death. Isn’t it time to take a look at these age-old traditions to figure out how they are hurting the people?

Similarly, housing construction is still chaotic in many places on the continent and hygiene seems to be a foreign concept. It is normal to see a chain of Africans urinating on the streets as if they are in a competition. In many slums across the continent, many homes do not have toilets. Human waste is disposed of in a manner that is far from being pleasant. The people of this beleaguered continent seem to be imbued with a short term vision of life that is hurting them every step of the way and it appears only very people actually notice the health ticking time bombs that the people themselves have created. African countries seem to have chosen housing development models that make it impossible for their environments to be clean. When individuals build their own houses, they hardly factor in hygiene and the environment into the whole equation. The objective is always to have a roof over their heads and this explains why disgusting slums are a very visible and unpleasant presence on the continent, even in capital cities.

Also, the eating of wild animals considered as prime suspects in the spread of Ebola must stop if the people of this continent have to stop Ebola from rolling them back into pain and tragedy. Africans should be tired of shedding tears. They have been shooting themselves in the foot for too long due to bad habits and outdated traditional ways. The DRC hemorrhagic fever has the potential to erase entire families and villages if the right measures are not taken. For now, Africans have to learn how to accept new ways if they do not want to be deleted by these viruses that are determined to kill and give the continent a very bad name.

- Details

- Ngwa Bertrand

- Hits: 2745

The two US aid workers infected with the Ebola virus in Liberia have recovered and have been discharged from hospital, medical officials have said. Recovered patient Dr Kent Brantly thanked supporters for their prayers at a news conference. Nancy Writebol was discharged on Tuesday. The two were brought to the US for treatment two weeks ago.The outbreak has killed more than 1,300 people in West Africa, with many of the deaths occurring in Liberia.

"Today is a miraculous day," said Dr Brantly, who appeared healthy if pallid as he addressed reporters on Thursday at Emory University hospital.

"I am thrilled to be alive to be well, and to be reunited with my family. As a medical missionary, I never imagined myself in this position." He said Ebola "was not on the radar" when he and his family moved to Liberia in October.

Dr Bruce Ribner said after rigorous treatment and testing officials were confident Dr Brantly had recovered "and he can return to his family, his community and his life without public health concerns". The group he was working for in Liberia, Samaritan's Purse, said they were celebrating his recovery.

"Today I join all of our Samaritan's Purse team around the world in giving thanks to God as we celebrate Dr Kent Brantly's recovery from Ebola and release from the hospital," Franklin Graham said in a statement.

- Details

- Ngwa Bertrand

- Hits: 2601

Subcategories

Flourish Doctor Article Count: 3

Meet Your Coach Dr. Joyce Akwe ... With a master's in public health and a medical doctor specialized in internal medicine with a focus on hospital medicine.

Dr. Joyce Akwe is the Chief of Hospital Medicine at the Atlanta VA Health Care System (Atlanta VAHCS), an Associate Professor of Medicine at Emory University School of Medicine and an Adjunct Faculty with Morehouse School of Medicine in Atlanta GA.

After Medical school Dr. Akwe worked for the World Health Organization and then decided to go back to clinical medicine. She completed her internal medicine residency and chief resident year at Morehouse School of Medicine. After that, she joined the Atlanta Veterans VAHCS Hospital Medicine team and has been caring for our nation’s Veterans since then.

Dr. Akwe has built her career in service and leadership at the Atlanta VA HealthCare System, but her influence has extended beyond your work at the Atlanta VA, Emory University, and Morehouse School of Medicine. She has mentored multiple young physicians and continuous to do so. She has previously been recognized by the Chapter for her community service (2010), teaching (as recipient of the 2014 J Willis Hurst Outstanding Bedside Teaching Award), and for your inspirational leadership to younger physicians (as recipient of the 2018 Mark Silverman Award). The Walter J. Moore Leadership Award is another laudable milestone in your car

Dr. Akwe teaches medical students, interns and residents. She particularly enjoys bedside teaching and Quality improvement in Health care which is aimed at improving patient care. Dr. Akwe received the distinguished physician award from Emory University School of medicine and the Nanette Wenger Award for leadership. She has published multiple papers on health care topics.

Local News

- Details

- Society

Kribi II: Man Caught Allegedly Abusing Child

- News Team

- 14.Sep.2025

- Details

- Society

Back to School 2025/2026 – Spotlight on Bamenda & Nkambe

- News Team

- 08.Sep.2025

- Details

- Society

Cameroon 2025: From Kamto to Biya: Longue Longue’s political flip shocks supporters

- News Team

- 08.Sep.2025

- Details

- Society

Meiganga bus crash spotlights Cameroon’s road safety crisis

- News Team

- 05.Sep.2025

EditorialView all

- Details

- Editorial

When Power Forgets Its Limits: Reading Atanga Nji Through Ekinneh Agbaw-Ebai’s Lens

- News Team

- 17.Dec.2025

- Details

- Editorial

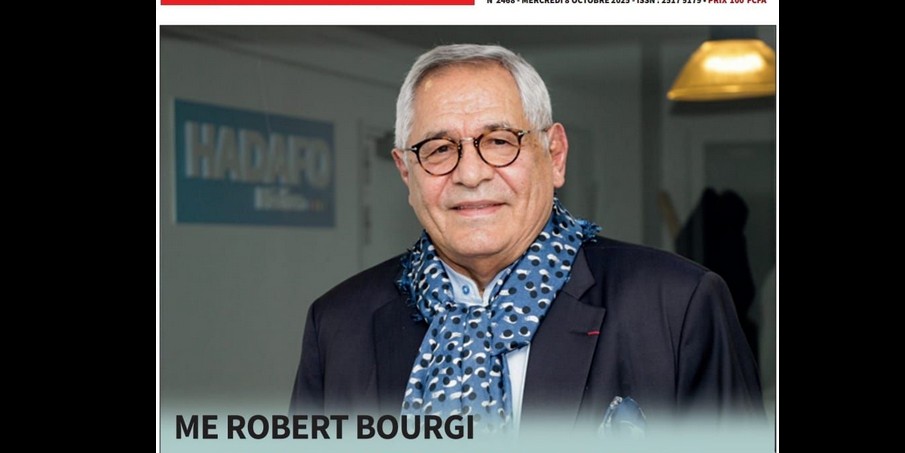

Robert Bourgi Turns on Paul Biya, Declares Him a Political Corpse

- News Team

- 10.Oct.2025

- Details

- Editorial

Heat in Maroua: What Biya’s Return Really Signals

- News Team

- 08.Oct.2025

- Details

- Editorial

Issa Tchiroma: Charles Mambo’s “Change Candidate” for Cameroon

- News Team

- 11.Sep.2025