- Details

- Politics

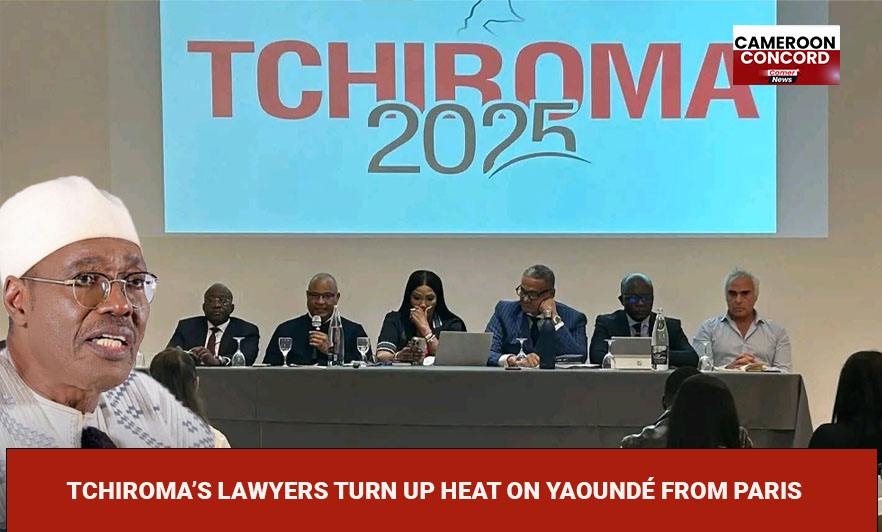

Paris Briefing by Issa Tchiroma’s Lawyers Piles Pressure on Yaoundé as Post-Election Disputes Escalate

[PARIS, Oct 23] – In a closely watched press conference at Salon Hoche in Paris, counsel for Issa Tchiroma Bakary, presidential candidate and leader of the Front for the National Salvation of Cameroon (FSNC), laid out their legal and evidentiary case for contesting the post-election narrative in Cameroon.

Framing the issue as both a constitutional dispute and a rule-of-law test, the legal team said their client’s victory—grounded in original, signed procès-verbaux (PVs)—must be recognized by the Constitutional Council, or the matter will escalate to regional and international forums.

The Paris event, staged far from Yaoundé yet targeted squarely at a global audience, sought to do three things at once: (1) formalize the campaign’s claims of a first-round victory on Oct. 12, (2) detail alleged irregularities by administrative and electoral authorities, and (3) warn that any final tally that diverges from the PV record will be challenged under domestic and international law. The lawyers argued that 18 departments, representing roughly 80% of the electorate, show Issa Tchiroma at ≈54.8% of valid votes against ≈31.3% for Paul Biya, with the remainder split among other contenders—numbers broadly consistent with the Transparency Series of PVs published in recent days.

Domestic law: Constitutional Council as the gatekeeper.

Under Cameroon’s 1996 Constitution and the Electoral Code, disputes over presidential results fall to the Constitutional Council, which examines petitions relating to irregularities, the integrity of the count, and the validity of PVs. The Council retains wide discretion over what evidence it admits and how it weighs alleged infractions. In 2018, it rejected multiple petitions—most prominently those led by opposition figure Maurice Kamto—holding that the evidence adduced did not meet the thresholds for annulling or altering the proclaimed results. That precedent looms large: any challenge today must marshal chain-of-custody proof for PVs, document specific polling-station-level breaches (e.g., expulsion of agents, tampering with returns, or unlawful aggregation), and tie those breaches to a material effect on results.

Comparative precedents: high bars, but not insurmountable.

While Cameroon’s courts have historically been reticent to overturn national results, comparative African jurisprudence shows that courts will act when the evidentiary record is robust and systemic flaws are proven. The Kenyan Supreme Court (2017) annulled a presidential election after finding irregularities in result transmission that undermined verifiability. The Malawi Constitutional Court (2020) set aside a presidential outcome on grounds of widespread tally anomalies and noncompliance with electoral law, later upheld by the Supreme Court. Ghana’s Supreme Court (2013), by contrast, upheld the result after a marathon petition where the burden of proof was not met. The lawyers in Paris cited these cases to argue that African courts can, and sometimes do, enforce strict compliance when presented with granular, verifiable evidence.

International standards and fora: pressure, not substitution.

The legal team underscored that while international law does not displace domestic jurisdiction, it provides benchmarks. ICCPR Article 25 protects the right to genuine periodic elections by universal suffrage and free expression of the will of the electors; the African Charter on Democracy, Elections and Governance and the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights demand transparency, equal suffrage, and effective remedies. In practice, however, the primary venue remains domestic: Cameroon has not accepted the individual-complaint jurisdiction of the African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights. Litigants may petition the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights or seek diplomatic/targeted-sanctions advocacy, but those tracks complement—rather than replace—the Constitutional Council process.

What would a viable petition need to show?

Seasoned election litigators who spoke to Cameroon Concord point to three pillars:

-

Documentary integrity: A comprehensive, indexed archive of original PV scans with verifiable provenance (polling-station codes, signatures/stamps, party agent attestations), matched to published tallies.

-

Materiality analysis: A polling-station-by-station or constituency-level demonstration that any irregularities, if corrected, would alter the outcome or fall outside acceptable error margins.

-

Causation and remedy: A clear legal theory connecting the breaches to specific remedies the Council can grant—ranging from redress in defined localities to national recounts or, in extreme scenarios, annulment and rerun.

At the Paris podium, Tchiroma’s lawyers claimed they have already met these tests, citing thousands of PVs that they say align with the published Transparency Series. They pledged to file or supplement petitions within the statutory window before the Council’s expected proclamation (anticipated by Oct. 26), warning that any certification at odds with the PV record would be prima facie unlawful.

Politics intrudes: the “Prime Minister” overture and its legal optics.

The team also referenced reports—circulating since this week—that envoys linked to President Paul Biya floated a Prime Minister offer to Tchiroma as a political off-ramp. From a legal-institutional lens, such overtures can be read two ways: either as an attempt to stabilize the polity ahead of final results, or as an implicit acknowledgement of contested legitimacy. Tchiroma has publicly rejected the idea, framing it as incompatible with the PV-based claim to the presidency. Whatever its merits, the gambit complicates the Council’s tightrope walk between legal formalism and political reality.

Risk calculus for the Council.

If the Council follows its 2018 posture, it will demand near-forensic proof of fraud or material irregularity and may decline to disturb the administrative tally. But the present cycle differs in two ways: (i) a widely disseminated, verifiable PV archive has emerged in real time; and (ii) street pressure across the Grand North—Garoua, Maroua, Ngaoundéré, Guider, Kaélé—has escalated as of Oct. 23, amid reports of connectivity throttling and tense policing. In that climate, a judgment that ignores the documentary record could deepen the legitimacy crisis; conversely, an order that compels targeted reviews or publishes detailed reasoning for each rejected claim could restore some confidence.

Bottom line.

From Paris to Yaoundé, the legal and political clocks are converging. On the evidence outlined by Tchiroma’s counsel—≈54.8% for Issa Tchiroma Bakary versus ≈31.3% for Paul Biya across 18 departments built from original PVs—the campaign asserts it has already cleared the 50% threshold and won outright. Whether Cameroon’s Constitutional Council will credit that record, demand additional verification, or hew to administrative tallies will shape not only this presidency, but the credibility of the system itself.

Meanwhile, tension continues to boil across Cameroon today (Oct. 23), with fresh daytime mobilizations in multiple northern localities and a hardening expectation—at home and abroad—that whatever result the state proclaims must match the PVs the public has now seen.

- Details

- News Team

- Hits: 471